By the early 19th century, the local middle classes had grown tired of sharing their wealth with Spain, and an obsession with independence began to grow.

In particular the Creoles (those born in New Spain of Spanish parents) resented being considered inferior by those born in the European homeland. They saw an opportunity in the Spanish war against Napoleon’s invasion of 1808.

The main protagonists of the Independence were the priests Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla and José María Morelos.

On September 16, 1810, Hidalgo freed the prisoners in the town of Dolores, locked up the Spanish authorities and called the people to rebel by ringing the church bells. Hidalgo started out with 600 men, but soon had 100,000 and overran towns of central Mexico. Hidalgo was tricked, caught, and condemned the following year, and was executed by firing squad on July 30, 1811.

Morelos, from the western city of Valladolid (now Morelia) led successful campaigns in 1812 and 1813, which included the capture of the city of Acapulco, the then principal trading port on the Pacific coast. He was captured and shot on Dec. 22, 1815. Despite the setbacks, the independence movement continued under the Creole colonel Agustín de Iturbide. On September 28, 1821, the first independent government was named with Iturbide at the head.

Independence was followed by thirty years of great political turmoil, which included the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848 in which Mexico lost Texas, California, and New Mexico to the victors.

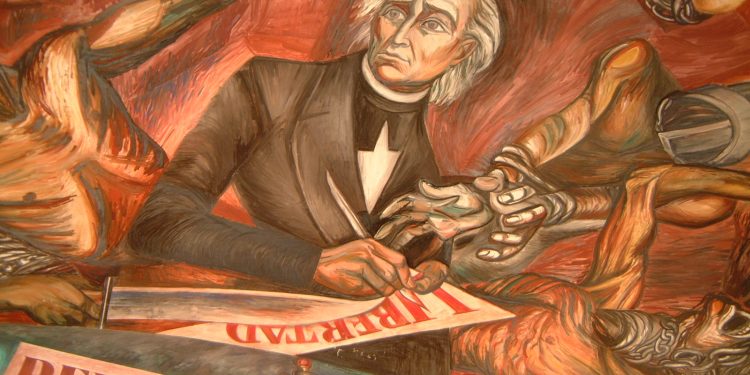

Then came a period of reform, led by the educated of the country. The liberal Benito Juarez, who would be elected president in 1861, promoted reform laws that were incorporated into the Constitution of 1857. As provisional president, he also reduced the powers of the Roman Catholic Church, and confiscated church property.

In 1864, Austrian Archduke Maximilian was made Emperor with the backing of Napoleon III. Maximilian ruled Mexico until 1867, when he was defeated and shot after Napoleon pulled out his troops to fight a war with Prussia. The return to government of Juarez is also known as the Restoration of the Republic.

The Juarez years were followed by the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz, a military leader who was president from 1876-1880 and 1884-1911. Mexico underwent a period of unprecedented economic development under Diaz, with the construction of railroads, ports, and telecommunications. But Diaz’s repressive government and the increasingly wide gap between rich and poor, coupled with Diaz’s courting of foreign investors and large landowners, led to discontent and uprising after he won yet another election in 1910—his sixth consecutive re-election.

The 1910-1917 Revolution was started by Francisco Madero, a democratically minded politician who was opposed to re-election. With military uprisings by Francisco Villa (or “Pancho” Villa as he is commonly known) in the north, and Emiliano Zapata in the south, Diaz was soon forced to resign and go into exile. Madero became president, but his army chief Victoriano Huerta staged a coup in 1913 and had him killed. Huerta stepped down in 1914, and Venustiano Carranza become president.

While few Mexicans question the importance of the birth of an independent nation after three centuries of colonial rule, the 1910-1917 period of conflict that led to the promulgation of the 1917 Constitution was far more complex, and to a certain extent inconclusive. A number of the better-known heroes of the Revolution were themselves killed in acts of treachery well after 1917: Emiliano Zapata in 1919, Venustiano Carranza in 1920, Francisco Villa in 1923, and Álvaro Obregón in 1928.

Disagreements continue to this day on the significance of the events that made up the Revolution, with ideas usually influenced by political views. The revolution is not the same thing seen from the left as from the right, and its success or failure from either of those viewpoints is not something that can be easily settled. The Wikipedia article (Spanish) illustrates how complicated a matter it was.

A new Constitution was promulgated in 1917 which, among other things, restored communal land to the Indian population and renewed the anti-clericalism of the Juarez years.

Next: Modern Times

Mexico in your inbox

Our free newsletter about Mexico brings you a monthly round-up of recently published stories and opportunities, as well as gems from our archives.